For disposal of invasive plants and other weeds, my preference is to compost them in the same general area in which they grew. Scattered compost piles in the backyard forest help return essential elements to the soil and save having to haul invasive debris farther away.

Composting is not a good option for invasives in their reproductive stage, because small compost piles don’t usually generate enough heat to kill seeds. In this case, the best option is to dispose of them in yard waste disposal bins since the debris will be composted in facilities required to hold compost temperatures hot enough and long enough to ensure pathogen reduction, thereby also killing seeds. Thus, the seeds of invasive plants added to yard waste disposal bins don’t create problems elsewhere.

Lacking a yard waste disposal bin, weeds in the reproductive stage are best bagged and trashed, especially those that germinate prolifically from seed. If they are disposed inside a restoration area, and even a few seeds germinate, they are likely to completely repopulate the area from which they were removed. For invasives that spread primarily by rhizomes or runners, however, I admit to sometimes composting them within invasive plant containment areas. For example, I recently began surrounding a large patch of Yellow Archangel with a Bradley Line to keep it from spreading, and began composting the invasive debris inside the containment area.

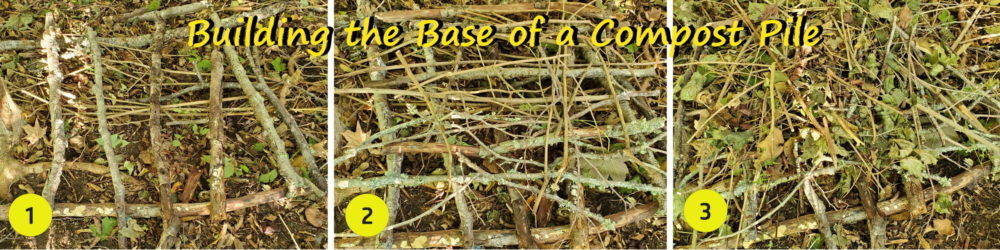

On all of my compost piles, to prevent the invasive plants from touching bare soil and continuing to grow, I follow Forterra’s instructions and start with a base of fallen limbs, cut or broken to length, and stacked in three or four crisscrossing layers. Like building a fire, the base also enables the essential flow of air through the pile since decomposition and combustion are similar in terms of chemistry. In both, energy (heat) is released as oxidation breaks apart carbon-hydrogen bonds in large organic molecules to form simpler molecules including carbon dioxide, water, simple sugars, and mineral salts.

With fire, oxidation proceeds rapidly, releasing the extreme heat needed to keep combustion going. With composting it occurs slowly, as bacteria, fungi, and other microbial organisms metabolize organic matter, and ideally producing just enough heat to maintain a suitable environment for the composting organisms. However, if compost piles are too dense and deep, the heat generated can be enough to spontaneously combust.

Once, I kept adding Ivy to the same compost pile for several months in a row until it was a dense mass about 8’ high and 20’ across. Shortly thereafter, I came back to find it completely burned to the ground. I think it must have spontaneously combusted. Now I try to keep compost piles less than 5’ high, because I want them to generate enough heat to keep the decomposition processes going, but not enough to combust and start a fire in the forest.