As we weed our backyard forests and their edges, we are constantly making decisions about which plants to remove (most of the non-natives) and which to allow (almost all of the natives). For some plant species those decisions are complicated by various factors, and different restoration practitioners may have different, legitimate opinions. For some plants, I think it’s ultimately up to each of us to decide for ourselves what to remove and what to allow. In this blog, I write about five such plants and why I have decided to remove some and allow others.

Three Plants I Remove

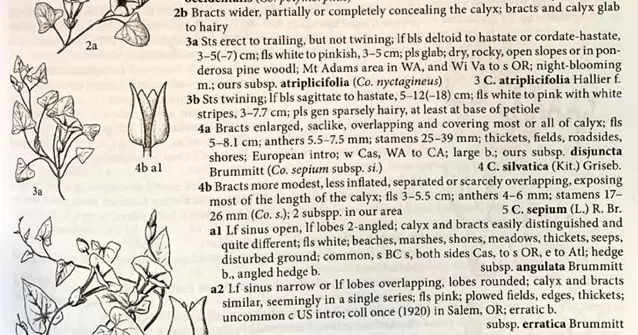

Hedge Bindweed

I continue to remove Hedge Bindweed before it blooms, despite the existence of a less-common, less-aggressive, native subspecies (Calystegia sepium ssp. angulata), that can’t be identified until after it sets buds. My rationale is two-fold. First, is its rarity. As of this post, there have been no iNaturalist reports of angulata in our region. Second, in terms of preserving biodiversity, I’ve decided that subspecies are generally close enough. In other words, I doubt that there are many species of invertebrates adapted so narrowly to a plant subspecies that they can’t make do with plants of the same species.

Shotweed

I came to the same conclusion on Shotweed as for Hedge Bindweed. The native (though a separate species) is rare in our region and can only be identified after it blooms.

Self Heal

Like Shotweed, I’m pulling this one when I find it creeping across my Bradley lines into the adjacent forest despite the existence of a native subspecies (Prunella vulgaris ssp. lanceolata). According to the Jepson eFlora, its leaves are narrower and stems more erect that the abundant Eurasian Self Heal. (Note that a few “research grade” sightings of lanceolata have been reported for the Puget Lowlands in iNaturalist.)

Two Plants I Allow

Stinging Nettle – Urtica Dioica

I allow Stinging Nettle to grow in most places, despite the widespread non-native subspecies. The USFS Fire Effects Information System, states that the Urtica genus has “a confusing taxonomic history” but apparently in North America just one species (dioica) with three subspecies. Two of those subspecies are native, the other European. Telling them apart is not easy. Unlike Hedge Bindweed, Stinging Nettle, though aggressive and widespread, is not considered invasive. In terms of biodiversity, I think it makes sense that native invertebrates can likely get by on the European subspecies.

Sweet-Cicely – Osmorhiza Berteroi

When Sweet Cicely appeared in Forest Park a few years ago and quickly began to spread I wanted to make sure it was native because it would have been difficult to eradicate. I learned that there are quite a few species of Osmorhiza around the world, but for now it sounds like the only non-native species to watch out for in our region is naturalized European Sweet Cicely (Myrrhis odorata) which is much more lush than our local native.